Meaning, the Cryptid

On Bigfoot, Zen, and hillbilly hopes.

Warning: Weird and highly speculative post.

It’s been wryly observed that existent animals are in many cases stranger than the ‘legendary beasts’ people on the discovery channel scour the woods for. Yet I sympathize with the Bigfoot hunters! Who hasn’t marveled at the possibility of Loch Ness monsters and giant apes, and thought it self-evident that the discovery of these creatures would bestow the world, or at least their corners of the world with a bit of magic, even meaning, importance?

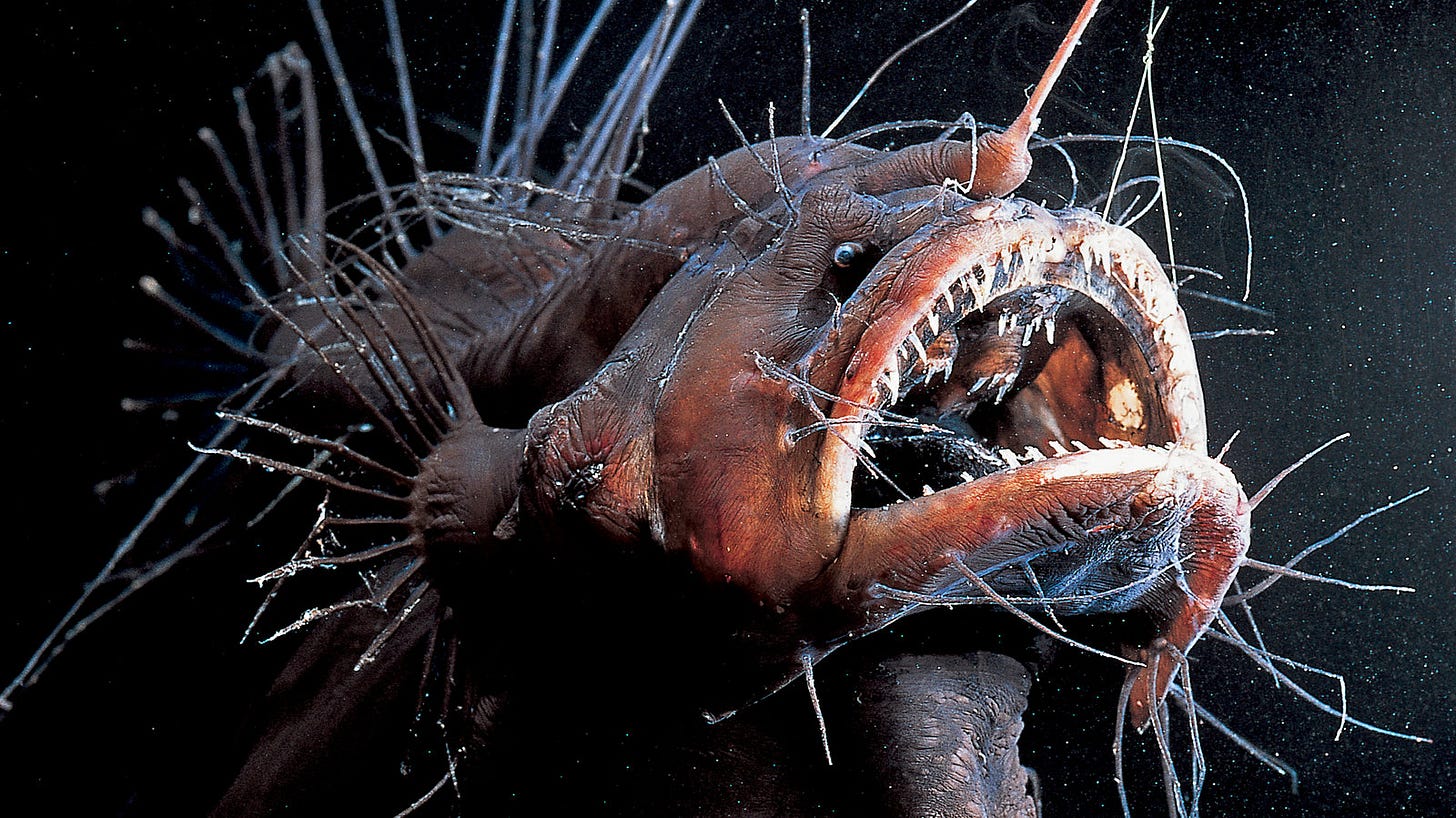

But then I step back and consider colossal squids, blue whales, and spider crabs, only to realize that if what I’m hoping for is bone-chilling horror at the unknown, then the angler fish more than delivers, and if what I’m seeking is the sense that another great intelligence shares this earth with us, then the cetaceans seem to answer the call, what with their names, songs, and thousands of apparent phonemes. So why this longing?

It is a great shame that Portuguese Man-O-War, and Platypuses, for their being undeniably real, fail to provide the deeper sort of life-affirming wonder that most bigfoot seekers seem to be after. For there is a sense in these seekers, as in me, that a world with bigfoot, (and of course, those most spiritually-uplifting of cryptids, The Aliens) would be far more meaningful than the one we currently occupy. All this by the same occasionally self-conscious, but usually instinctual and innate longing for the unreal that makes us feel that Middle Earth is more meaningful than The Real Earth, and that the presence of a great many omnipotent or at the very least ‘magical’ beings make it so.

This strange fact, that these elusive and by all appearances non-existent creatures would make our world more meaningful, and that the obviously real and at face value, more incredible animals fail to do so, has caused me to consider my own very real sense of longing for a god, and a justification of human life in particular.

I used to think that every honest and introspective atheist shared this longing, but by now I’ve heard enough to know I was totally mistaken, and that a great many people are able to let bygones be bygone, so far as the absence of god and meaning is concerned. However, I’m not one of them. So here we are, considering the cryptid.

Or, to be more precise, considering the longing for cryptids of all kinds, and the mechanism by which a thing is judged as useless, spiritually speaking, for committing the simple crime of being undeniably real.

Is this perverse and insatiable desire for the non-existent, for the very fact of its being non-existent, not what Zen points to as the fundamental human problem? Not that the existence of aliens would be impossible or unimportant, but that it would lose its significance as soon as they entered the world of the everyday, the known, and could be studied in textbooks alongside whatever reptiles they might happen to resemble? But then what would the textbook-reading children hope to find, that would make their alien-filled world cease to be so mundane, so empty, so merely biological? Gods, maybe? Are Zen masters not attempting to obliterate this very desire by saying things like ‘The Buddha is that shit-stick lying on the ground’?

Anyone who believes their craving for meaning would be satisfied by an exacting description of the nature of god, as well as proof of his existence, should give Chris Langan’s CTMU a good, long, read. It seems that anything sufficiently complex to govern the universe, or even to take moral interest in the lives of human beings becomes quite a different thing if actually apprehended. What’s the use of a god you understand, in the manner of an internal combustion engine? Further, what value would your belief in him have if it was not predicated on faith in an unknown? For it’s this very faith that delivers the comfort, and the flying in the face of everyday randomness and dearth of meaning that forms the basis of a relationship between a human being and this invisible other. Only Kierkegaard seemed capable of understanding this and using it as fuel for his faith, rather than as an impediment to unreason. Personally I prefer the response of the Zen masters, who believed this human craving for that which is not could be cut off at the root, simply by the realization of the self as only another non-existent thing we hope for, rather than a lonely entity in constant need of spiritual succor, and subject-object interplay. But even that is another red herring, as by all reports enlightenment isn’t constant joy, nor union with god, nor simply a wonderful time that lasts forever: it’s nothing less than the cessation of this desire for cryptids, for things we feel to be ever lurking behind treelines, just out of sight but full of promise, and capable of making our time in the woods feel significant.

Would Zen masters and William James not say that the experience of looking at a tree with Bigfoot behind it, and one without, is exactly the same? And isn’t it the same situation in regards to god? This present universe is what it is, and the facts of it do not change in retrospect given our knowledge of its creator or countless invisible forces. A thing described is a thing dead and thrown aside by the parts of us that crave meaning—no wonder it took so long for us to come to science as a means of deducing truth! To trade wonder at the unknown, and perfect confidence (because how could primitive man not believe in gods, spirits, monsters) in the existence of things wondrous, for an expansion in all that was known, and to effectively butcher the unseen world in the way of a kill—why should they have wanted to make that trade? And why should we want to make it?

No doubt modern human beings will continue, like stubborn WWI infantry, to retreat and entrench themselves behind mysteries so absurd no one can even attempt an explanation of them. And of course! If astrology is so beyond the pale of explanation that no one dares approach it, that means it’s safe from the encroachment of knowledge upon hope. Because that is what makes the bigfoot hunters endearing, and notable as extreme manifestations of this drive we all share—a drive towards the greatest windfall imaginable, that of undeniable reassurance that this tree, this forest, this patch of sky, this universe, is the secret home of things that do not exist, and so can never be denied nor assimilated into the realm of mere knowledge, and law.

It is this hope that will likely keep our will towards the mystical alive forever, though in the future we will stand on tiptoes atop the last eroded island of unknown things amidst the ever-encroaching sea of knowledge, holding onto god, or freewill, or crystal-healing, or whatever the last holdout may be.

But if astrology were real, and could provide accurate forecasts of future prospects and moods, it would offer its believers no more comfort than their therapists and CNN might.

And if Bigfoot were real, it would do no more for the spirits of strange Appalachian men with long beards and camcorders than the gorillas lounging lazily at zoo.

The real, being necessarily contained and constrained by all else that is real, can offer no transcendent hopes, nor justifications. The woods are the woods, no matter what lurks within them. The unknown and unseen offer hope because we are creatures evolved to turn over rocks in hopes of finding food. But once a rock is flipped, and the grubs found or not found, the hope, by necessity, must vanish.

Lovely, dark and deep. To be honest: I expected sth. about "Disco Elysium" - which has a cryptid-side-quest. :D https://erikhoel.substack.com/p/the-future-of-literature-is-video

On encountering the cryptid, one might be able to talk to it; when one asks: Are you the "miracle"? - it answers: No. You humans are the miracle.

>it would offer it’s believers

Typo, "it's" should be "its".