The writing of Ryszard Kapuscinski's journalistic opus The Emperor was inspired not by the 1974 overthrow of the thousand-year-old Ethiopian empire, nor the figure of Halie Selassie as an emblem of an endlessly corrupt and instable sub-Saharan Africa—it was if you can believe it, inspired by a small Japanese dog named Lulu. In search of an angle on the story,

[Kapuscinski] fell into a deep depression. “But, as often happens in such situations, a flash of light finally went off in my head”. He sought for a small significant detail, and there suddenly came back to him the image of a tiny dog on Haile Selassie’s lap. A Palace servant had said to him: “It was a little Japanese miniature dog, and its name was Lulu.” Kapuściński goes on: “When I had that absolutely simplest of sentences, I knew I had a book.”

The dog probably looked something like this:

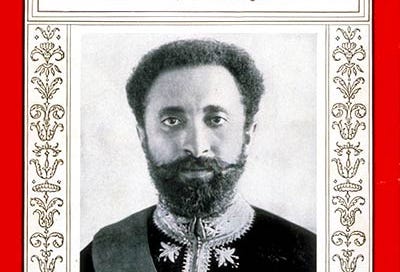

Which provides a strange contrast to the aesthetics of Selassie and his court:

Lulu’s role in court life serves as a good entry point into the heart of the slow tragedy that took place in Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974, when Haile Selassie, the last of a thousand-year empire, ruled. As told by the dog’s royal attendant:

“[Lulu] was allowed to sleep in the Emperor’s great bed. During various ceremonies, he would run away from the Emperor’s lap and pee on dignitaries’ shoes. The august gentlemen were not allowed to flinch or make the slightest gesture when they felt their feet getting wet. I had to walk among the dignitaries and wipe the urine from their shoes with a satin cloth. This was my job for ten years.”

Kapucinski’s story of the royal court and its overthrow by a fairly bog-standard military coup is told through monologues from various courtiers whom Kapuscinski sought out in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, as the ashes settled after the ridiculously evil-sounding ‘The Derg’ consolidated power following Selassie’s overthrow.

These are the collected recollections of ministers, administrators, valets, pillow-bearers(!), and everyone in between, who when taken together create a portrait of a court and ruler so cartoonishly bombastic, corrupt, atavistic, and Kafkaesque as to defy belief. It’s tempting to pluck out all the ridiculous tales of excess that follow in the vein of the Lulu pee-wiper’s story, but as entertaining as it is to read about an Emperor in the year 1973 throwing meat to his lions every morning as supplicants beg him for literal gold coins may be, what’s more interesting is the more universal, almost elemental aspects of court life as portrayed here.

This book can be read as a time traveler’s journal, a sober and thoroughly modern journalistic record of things that might have taken place in the palaces of Hammurabi, Charlemagne, Caesar, or any other despotic monarch, benevolent or otherwise.

Unfortunately, we do not find here the realized Neo-reactionary dream of an august and secure ruler, who with endless freedom to select the cream of his country, creates a ruling class that embarrasses the spineless, sycophantic, election obsessed elites of democratic nations. Quite the opposite, actually:

I’ll come right out and say it: the King of Kings preferred bad ministers. And the King of Kings preferred them because he liked to appear in a favorable light by contrast. How could he show himself favorably if he were surrounded by good ministers? The people would be disoriented. Where would they look for help? On whose wisdom and kindness would they depend? Everyone would have been good and wise. What disorder would have broken out in the Empire then! Instead of one sun, fifty would be shining, and everyone would pay homage to a privately chosen planet.”

Status-obsession was the alpha and omega of this court, the fuel behind each and every interaction, decision, and absurdity. The single-mindedness of the emperor and all his courtiers renders all the fragments of court life as hilarious as they are pathetic and in a strange way, quite sad because there are so few nuances to their dealings— it’s naked self-interest all the way down. Everything is surface-level, obvious, shameless. I hesitate to even call the courtier’s manipulations machiavellian because they hardly reach that level of sophistication.

The following describes the wave of anxiety that swept through the court whenever the list of accompanying courtiers was submitted to the emperor preceding one of his many trips abroad:

“And when everyone possible had been squeezed in and the list determined, pushing and undermining and elbowing began anew. Those who were lower were determined to rise. Number forty-three wanted to be twenty-sixth. Seventy-eight had an eye on thirty-two’s place. Fifty-seven climbed to twenty-nine, sixty-seven went straight to thirty-four, forty-one pushed thirty out of the way, twenty-six was sure of being twenty-second, fifty-four gnawed at forty-six, sixty-three scratched his way to forty-nine, and always upward toward the top, without end. In the Palace there was agitation, obsession, running back and forth through the corridors. Coteries conferred, the court thought of nothing but the list until the word spread from office to salon to chamber that, yes, His Highness had heard the list, made wise and irrevocable corrections, and approved it. Now nothing could be changed and everyone knew his place. The chosen ones could be identified by their manner of walking and speaking because on such an occasion a temporary hierarchy came into being alongside the hierarchy of access to the Emperor and the hierarchy of titles. Our Palace was a fabric of hierarchies…”

The revelation that the royal court of a thousand-year empire resembles nothing so much as a particularly vicious public high school is shocking, but also kind of convenient, in a way. It made it very easy to wrap my head around the baroque power dynamics that suffused the courtiers’ day-to-day lives. But once you see court life dissected as it is in this book, it’s hard not to see how its structure is in many ways the most common pattern of social organization. It strikes me that ‘courts’ are the default mode of human political life and that anything better or nobler than a gang of sycophants scrambling for favor around one or a few very high-status individuals is a rare and beautiful thing.

I can recall in high school the ‘courts’ that would pop up whenever someone had access to alcohol. Girls and boys alike would sit closer to said alcohol-access-point-person, lean into them, laugh harder at their jokes, increase their social proximity to said person whenever possible, both grasping at and showing off their special relationship with the emperor of that moment—and for that matter, it was much the same in elementary school, when one kid had a toy or treat that others wanted. People everywhere default to violence, or court life, when in groups of people between whom resources and status are distributed inequitably.

I think this explains a tendency my friends and I had to put on exaggerated British accents whenever entering an even slightly tense negotiation about money or anything else—we’re aping the exaggerated image of court life we, as Americans, tend to carry around in our heads, because at that moment, we’re establishing a court. I guess the self-parody helped ease the tension. And though the status gap was nowhere near what exists between an African Emperor and his subjects, there was a gap nevertheless, which inspires in high schoolers exactly the feelings described here by a Selassie courtier:

Everyone wanted very badly to be noticed by the Emperor. No, one didn’t dream of special notice, with the Revered Emperor catching sight of you, coming up, and starting a conversation. No, nothing like that, I assure you. One wanted only the smallest, second-rate sort of attention, nothing that burdened the Emperor with any obligations. A passing notice, a fraction of a second, yet the sort of notice that later would make one tremble inside and overwhelm one with the triumphal thought “I have been noticed.”

Replace ‘Emperor’ with ‘beautiful women’ and it becomes clear that this is not merely a record of one empire’s downfall, nor merely a way for a clever Polish journalist to scathingly criticize the cronyism of the Soviet Union without losing his job, but a substantial exploration of status-seeking as a primary prerogative of man.

Selassie’s courtiers were the last of a dying race that once ruled the world, and in them, we can see the forces that rule us, as well as what now works against them: the institutional and cultural counter-forces that have developed post-enlightenment in order to keep our instincts towards rabid status-seeking and pillage-via-the-state in check.

Or maybe I’m overly optimistic and those instincts are just better camouflaged by liberal systems of governance.

The people Kapuscinski interviews make it clear that there were essentially no pathways to status outside of the Emperor’s goodwill, and the Emperor himself liked it this way, and thus he gave the boot to anyone incorruptible because those not enriching themselves through the state were not sufficiently reliant on his favor, and so potentially disloyal.

A few of the more self-reflective speakers in the book grasp that the Emperor’s monopoly on any and all personal advancement for the elite class had something to do with the downfall of the state. Basically, the Emperor began allowing the children of elites to be educated abroad and expanded the educated-elite class to a point where there weren’t enough corrupt-petty-bureaucrat-type-posts to go around, and so the educated-elite class got uppity and began demanding liberal reforms, which the Emperor refused to provide at a fast enough clip, which dissatisfaction led to tales of the court’s decadence spreading to the common people, which made it rather easy for an underfed and underpaid army to turn sour against the Emperor and follow a council of military leaders to stage a coup.

…his Benevolent Majesty gradually lost control over this craze that possessed our youth. More and more of these youngsters ventured to Europe or America for their studies, and—how else could it have ended?—after a few years the trouble started. Because, like a wizard, His Majesty breathed life into the supernatural destructive force that comparison of our country with others proved to be. These people would return home full of devious ideas, disloyal views, damaging plans, and unreasonable and disorderly projects. They would look at the Empire, put their heads in their hands, and cry, “Good God, how can anything like this exist?” Here you have, my friend, another proof of the ingratitude of youth. On the one hand, so much care was taken by His Majesty to give them access to knowledge and on the other hand his reward in the form of shocking criticism, abusive sulking, undermining, and rejection. It’s easy to imagine the bitterness with which these slanderers filled our monarch. The worst thing is that these tyros, filled with fads unknown to Ethiopia, brought into the Empire a certain unrest, an unnecessary mobility, disorder, a desire for action against authority, and it is here that the ministers who were not distinguished by quick wits or perspicacity came to His Distinguished Highness’s aid.

It seems that for developing countries with authoritarian governments, the rate at which you expand your highly educated (especially western-educated) upper-middle and upper class is extremely important. If you have no ladders of status available for those people to climb, they fast look to making those ladders for themselves, which often involves blowing up the state and installing a new one. China seems to have succeeded here and managed to grow their college-educated class roughly in step with their expanding capitalist economy, such that a reasonably satisfied middle class developed.

Following what happened in 1989, where dissatisfied college students, much like those in Ethiopia rose up and then were crushed by a loyal military, there’s been very little public protest, and I doubt that’s purely a result of fear—there are very few visible signs of strong dissatisfaction in the upper-classes of China, though that may change as the CCP cracks down on its billionaire class, and basically asserts that they, much like the Ethiopian Empire, get to decide exactly who gets to enrich themselves and to what degree.

It may be that that in large, militarized countries with a disarmed populous, the loyalty of the military is all that really matters, but it’s clear that in Ethiopia the educated class exploded in numbers, and then came back to a country that was in many ways stuck in the middle ages. And though I feel comfortable in assigning most of the blame for this on Selassie himself, there are passages that make me surge with empathy for anyone attempting to rule over a country so resource-poor and in all ways undeveloped. Take, for example, this courtier’s take on the prospect of Selassie’s visiting poor provinces.

[Suppose that] today he would surprise the province of Bale, in a week the province of Tigre. And he notes: “loafing around, filthy, black with flies.” He summons the provincial dignitaries to Addis Ababa for the Hour of Assignments, scolds them, and removes them from office. News of this spreads throughout the Empire, and what is the result? The result is that dignitaries stop doing everything except looking at the sky to see whether His Distinguished Highness is coming. The people waste away, the province declines, but all that is nothing compared to the fear of His Majesty’s anger. And what’s worse, because they feel uncertain and threatened, not knowing the hour or the day, united by common inconvenience and fear, they start murmuring, grimacing, grumbling, gossiping about the health of His Supreme Highness, and finally, they start conspiring, inciting others to rebel, loafing, undermining what seems to them an uncharitable throne—oh, what an impudent thought—a throne that won’t let them live.

So for all intents and purposes, the Emperor is a tourist in his own country, experiencing the countryside as a westerner experiences North Korea on a state-supervised tour.

Imagine if Selassie made such a surprise visit, found the conditions unacceptable, but instead of firing the governor, offered to promote him to the governorship of a larger province if in three years there were some measurable improvements. To make that possible, some sort of census and province-outcome-measuring organ of the state would need to be established. So then whoever controlled that organ would have control over which governors got promoted, and likely governors of larger provinces would have an advantage in courting said census-minister, and so the most powerful governors who were most willing to fake their province’s data would grow in power, whilst competent governors of smaller provinces would be unable to compete, and would lose their jobs once the Emperor saw how pathetic their numbers were.

I played this game with myself a lot, as I read, and by the end of the book, I could no longer understand how any highly-centralized state ever managed to hold itself together for any length of time, especially before near-instantaneous communication was possible. Imagine the incentives faced by the Governor of a Roman province, with no one more powerful than he for 500 miles, and communications from his higher-ups taking weeks if not months to get through. Perhaps we underrate ancient people’s obsession with honor as a sort of fail-safe against the bounteous opportunities for rampant corruption faced by even the pettiest mayors of the tiniest mud-hut towns since the dawn of civilization. Though outside of East Asia, I don’t see strong evidence that societies with strong cultures of honor tend to have better bureaucracies than those without. It’s tempting to compare Ethiopia with, say, Japan, but then I think about Russia and Spain in contrast to say, Denmark, and realize that historical cultures of honor probably have little actual predictive value in regards to future metrics for corruption. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find any studies that looked at this relationship.

What does seem clear, a bit shockingly, is that for all of Kapucinski’s courtier’s gushing about the Emperor’s genius and divine stateliness, the loyalty of any given courtier seems to have been bought rather expensively with riches, and opportunities for extracting riches from Ethiopia’s starving populous of mostly farmers.

I say shockingly because Selassie was heir to a thousand-year empire never colonized by European powers except for Mussolini’s fascist Italy (which helped Selassie garner international favor and support, largely off the back of this appearance before the United Nations—peruse the comments for confirmation that the Emperor still has many fans from around the world). You would think he, of all monarchs, would have a kind of credibility and undeniable right-to-rule that wouldn’t necessitate propaganda, or the shameless loyalty-buying through the distribution of spoils to lackeys, in order to keep power. Yet the Selassie depicted in this book struck me as kind of pathetic, like a rich kid who keeps his friends around with gifts, and sows the seeds of further resentment in said friends by making them grovel and beg. And yet he ruled for thirty years, despite not only rampant corruption but multiple famines of a bone-chilling, biblical-proportions kind.

According to Wikipedia’s long, clinical list of Ethiopian famines, Sellasie oversaw three major ones, in 1958, 1966, and 1973, this last apparently being the worst and a major contributing factor in his overthrow. A documentary was produced by members of the foreign press on the 1973 famine, depicting:

…Thousands of people dying of hunger, and next to that His Venerable Highness feasting with dignitaries. Then he showed roads on which scores of poor, famished skeletons were lying, and immediately afterward our airplanes bringing champagne and caviar from Europe…

The courtier recounting this outrage gives a defense of his Emperor, founded in fact—Ethiopia is a country that has been plagued by famines for at least as long as its history has been recorded. But only an expert in Ethiopian geography and agriculture could suss out the degree to which this unfortunate history exonerates Selassie:

…death from hunger had existed in our Empire for hundreds of years, an everyday natural thing, and it never occurred to anyone to make any noise about it. Drought would come and the earth would dry up, the cattle would drop dead, the peasants would starve. Ordinary, in accordance with the laws of nature and the eternal order of things.

The most recent Ethiopian famine was…now, actually, in the northern province of Tigray. And before that, famines in 2003 and the mid-1980s killed more than a million people, dwarfing those overseen by Selassie. This begs the age-old questions surrounding the development, or lack thereof, in sub-Saharan Africa. Explanations for this stagnation seem to be everywhere, and offered by everyone, the most widely admired and accepted being that presented by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, perhaps in part because it’s a cozy, kindly explanation that leaves no ethnic group or nation feeling inherently superior or inferior to another, which is a good thing, I suppose, though it’s hard not to feel suspicious of explanations that leave everyone feeling secure in the quasi-Rosseuian modern ideas about how our environments, and not our genetics, are the primary determinant in both individual and collective development.

My reading of The Emperor has nudged me towards a ‘Great Man’ theory of the history of sub-Saharan stagnation and suffering. A succession of vicious aristocrats, who openly and self-consciously seek to extract as much from the peasants as they can, who leave the peasants only enough so that they can bear more children and harvest enough food so that a majority of them may survive until the next visit from the tax collector—this seems almost sufficient to me in explaining why Ethiopia, at least, is the way it is.

But don’t take my word from it. Let’s hear Selassie’s attitude towards his subjects, in his own words, recounted by a courtier:

…the people never revolt just because they have to carry a heavy load, or because of exploitation. They don’t know life without exploitation, they don’t even know that such a life exists. How can they desire what they cannot imagine? The people will revolt only when, in a single movement, someone tries to throw a second burden, a second heavy bag, onto their backs. The peasant will fall face down into the mud—and then spring up and grab an ax…he will rise because he feels that, in throwing the second burden onto his back suddenly and stealthily, you have tried to cheat him, you have treated him like an unthinking animal, you have trampled what remains of his already strangled dignity, taken him for an idiot…that, dear sir, is why His Majesty scolded the clerks. For their own convenience and vanity, instead of adding the burden bit by bit, in little bags, they tried to heave a whole big sack on at once. So, in order to ensure future peace for the Empire, His Majesty immediately set the clerks to work sewing little bags.

This from a relatively liberal, progressive despot, sincerely interested in the modernization and improvement of his country. One can only wonder at the attitude taken by other African leaders, who don’t even pretend to a paternal protectiveness over their subjects and are not whatsoever bound by tradition. And it’s not as if Selassie is likely to have come up with the above philosophy himself…it strikes me as an expression of ideas of previous Emperors, who saw the art of rule as the art of exploitation, of optimizing for the most efficient extraction of value from a static amount of labor and resources.

This is political rule as an extreme sport, where the leader seeks to extract as much as possible for himself and his cronies through the vehicle of the state, carefully toeing the line that if crossed might push the general populous or military towards violent revolution. I guess we can think of Selassie as a relatively adept sportsman…he lasted forty-four years, accumulated hundreds of millions in offshore bank accounts, and is still regarded as a hero by many, and even a god by some. In any case, he is rarely thought of in the same light as the Idi Admins and Robert Mugabes of the world, and after reading this, WWII notwithstanding, I think he probably should be.

The Emperor is a desperately sad book, about both the misery of ruling and of being ruled, as well as the pathetic, adolescent status games that are unfortunately the apparatus by which many countries, businesses, institutions, and informal associations are ruled. We as humans, if socialized above the level of brute force, tend to organize ourselves into vapid cliques wherein our intelligence is used primarily for adept navigation up the ladder of status—unless, through exacting institutional design or cultural taboo, incentives have been aligned so as not to give rise to court life. It wouldn’t surprise me if human intelligence developed out of an arm’s race between brains trying to outmaneuver each other within the bounds of the primitive ‘courts’ that would arise within any given tribe of apes.

If nothing else, from this book I’ve gained a new appreciation for the political thinkers of the enlightenment, from Locke to Voltaire, to Jefferson, to Rosseau—and now see their writings as a kind of intellectual crusade against the sorts of political systems that Kapuscinski so starkly puts on display in The Emperor. Not only because they are ineffective for reasons of accountability and incentive misalignment that the average business management student could diagnose at a glance, but because they are an affront to the dignity and self-ownership of all besides a small, and all-too-human ruling class of sycophants. I think enlightenment thinkers likely saw the courts that ruled them largely as Kapuscinski saw that of Ethiopia, and so were driven by righteous anger towards the development of something less, well, pathetic.

If you’re interested in other works by this author, check out this write-up by Matt Lakeman.

I have read The Emperor from my parents library (more like a stack of books), I love Kapuściński prose ever since. But apparently there was no Lulu, there is a real monster of a book detailing Kapuściński errors and confabulations: https://www.amazon.com/Ryszard-Kapuscinski-Life-Artur-Domoslawski/dp/1781680817 (In Polish the title is "Kapuściński non-fiction"), and most probably Lulu is one of them :(

I have not yet read that other book - it is too long, and probably quite boring (without any Lulus), but it is said to be well researched.

Thanks for the great review. It's good to see how far we've come in regards to corrupt elites and makes me hopeful the trend continues.